Author: Maya Lopez (Co-President)

When the 2025 Nobel Prizes were announced last month, Cambridge’s science enthusiasts and news junkies alike were buzzing with excitement, discussing the laureates, dissecting the research, and tallying college wins. However, I noticed less talk around a month earlier on the Ig Nobels”. Maybe because no Cambridge members were awarded this year? Or perhaps because it’s not serious enough?? … Whatever the reason, today we will take a break from all the rigidity of science and the recent serious concerns around politics contesting science. Instead, let’s take a look at the whimsical research that is also… seriously a science, which, as Nature once put it, “The Ig Nobel awards are arguably the highlight of the scientific calendar”.

Are Ig Nobel Prizes a real award?

This is one of the top Google searches with the keywords: “Ig Nobel prize”. The answer? YES*. It is a very real award with ceremony and all that has now been going on for 35 years. But “*” was not a typo as it is also, yes, a parody of the all-too-famous Nobel Prize, which probably needs no explanation of its own (hence the namesake and the pun of “ignoble”). For those of you who are unfamiliar, Ig Nobel is annually awarded by an organization called Improbable Research since 1991 with a motto of: “research that makes people LAUGH, then THINK”. This organization also publishes a “scientific humor magazine” (who knew that was a thing?) called Annals of Improbable Research (AIR), so they, in a sense, can be seen as a specialist that focuses on promoting public engagement with scientific research through fun. The Ig Nobel Prizes are often presented by Nobel laureates in a ceremony held at the MIT or other universities in the Boston area. Much like the “real” Nobel prizes, it has different award disciplines like: physics, chemistry, physiology/medicine, literature, economics, and peace, plus a few extra categories such as public health, engineering, biology, and interdisciplinary research. (The award categories do vary from year to year, though.) The winners are awarded with a banknote worth 10 trillion Zimbabwean dollars (a currency that is no longer used; roughly worth US$0.40), so it’s not really about the monetary value. They also get an opportunity to give a public lecture upon award, but researchers do face the risk of being interrupted by an 8-year-old girl (or, in the case of 2025, a researcher dressed up as one) crying “Please stop: I’m bored”, if it dares go on for too long. The ceremony, as you can imagine from here, has a number of running jokes, and if you are interested, you can watch the whole ceremony of 2025 on Youtube.

Bringing “in” science to the everyday curiosity:

So it’s a parody, yes, but the award does exist and is given to actual researchers. The quickest way to get a sense of the Ig Nobel might be to simply browse the list of research that was awarded prizes. This year, we’ve got:

| Category | Title | Reference |

| Aviation | Studying whether ingesting alcohol can impair bats’ ability to fly and also‹ their ability to echolocate | doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2010.02.006 |

| Biology | their experiments to learn whether cows painted with zebra-like striping can avoid being bitten by flies. | doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223447 |

| Chemistry | experiments to test whether eating Teflon is a good way to increase food volume and hence satiety without increasing calorie content | doi.org/10.1177%2F1932296815626726 patents.google.com/patent/US9924736B2/en |

| Engineering design | analyzing, from an engineering design perspective, how foul-smelling shoes affect the good experience of using a shoe-rack | doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2229-8_33 |

| Literature | persistently recording and analyzing the rate of growth of one of his fingernails over a period of 35 years | doi.org/10.1038/jid.1953.5 pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2249062doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1968.00300090069016 doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1974.00320210107015 doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4362.1976.tb00696.x doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1980.00330130075019 |

| Nutrition | studying the extent to which a certain kind of lizard chooses to eat certain kinds of pizza | doi.org/10.1111/aje.13100 |

| Peace | showing that drinking alcohol sometimes improves a person’s ability to speak in a foreign language | doi.org/10.1177/0269881117735687 |

| Pediatrics | studying what a nursing baby experiences when the baby’s mother eats garlic | pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1896276 |

| Physics | discoveries about the physics of pasta sauce, especially the phase transition that can lead to clumping, which can be a cause of unpleasantness | doi.org/10.1063/5.0255841 |

| Psychology | investigating what happens when you tell narcissists — or anyone else — that they are intelligent | doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2021.101595 |

I think the goal of “laugh and think” is clearly successful in all of this research. But speaking of thinking, some of these research topics made me wonder (and maybe you are too): “Why would you investigate that?” (What adult would?) or “Is this real, funded/published research”? What I want to highlight (and what may not be clear from the brief list on the Wikipedia page), is that they all have proper references attached to them. So yes, though their published titles might sound a bit more academic or “stuffy” (though often by not much), they are actual peer-reviewed papers!

Are you ridiculing science?

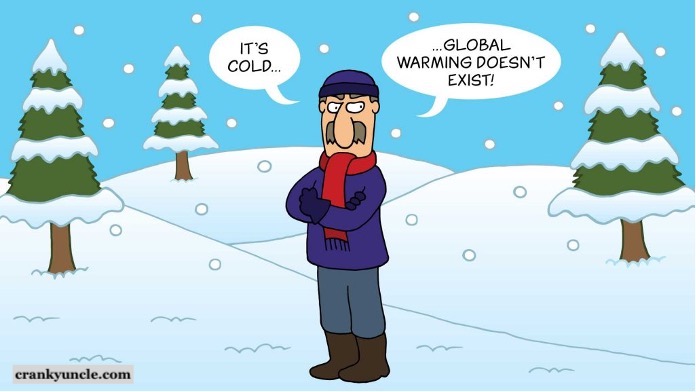

This question on the official FAQ page caught my attention, because I, as an IgNoble enthusiast, hadn’t imagined any serious criticism against these awards. Digging a bit deeper, I found that decades ago, the UK’s then-chief scientific adviser – Sir Robert May – made a formal complaint request that “no British scientists (should) be considered for an IgNobel, for fear of harming their career prospects”. (Note that the UK, alongside Japan and the USA (no wonder I’m acquainted with this prize), are regulars of this prize as a nation, winning awards nearly every year.) Furthermore, the article reads “He was particularly concerned when ground-breaking research into the reasons why breakfast cereal becomes soggy (by the University of East Anglia) won a prize,” essentially hinting at the concern of public ridiculing science (as a whole?). If you think about it, such a general attitude of “it’s not with the scientific investigation unless it’s clearly applicable/translatable/important” is perhaps far too typical, especially in basic sciences.

However, I think the founder of the prize, Marc Abrahams, had the best defence against the practice of “rewarding silly science”.

“Most of the great technological and scientific breakthroughs were laughed at when they first appeared. People laughed at someone staring at the mould on a piece of bread, but without that there would be no antibiotics… A lot of people are frightened of science or think it is evil, because they had a teacher when they were 12 years old who put them off. If we can get people curious and make them laugh, maybe they will pick up a book one day. We really want more people involved in science and I think the webcast will help do that.”

Slightly on a tangent, but “Maths Anxiety” is a recognized experience that many develop during childhood. While no research might exist on this (yet), I also suspect a similar phenomenon with STEM at large. Sometimes I get comments from students taking humanities subjects (even in Cambridge!) like “wow, you’re doing a real/serious degree”, or “science sounds so difficult”. For some people, “being put off” by science might trace back to a negative experience during their first formal introduction to science as a subject in school. In that case, bringing their interest back to science with all-serious demeanor and stuffy topics might be quite a high barrier to cross. However, looking at the Ig award list from earlier, and how quickly they make you go “huh” after the laugh, I can’t help but think that these funny, curious studies might be the push they need to ignite their curiosity and welcome them back to scientific inquiry without any pressure.

The satire (and controversy?) of IgNobel

That being said, not all IgNobel prizes were specifically awarded to quirky “research that cannot (or should not) be reproduced”. It was also sometimes awarded as a satire. In the recent case of 2020, Ig Nobel Prize for Medical Education was awarded to Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil, Boris Johnson of the United Kingdom, Narendra Modi of India, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico, Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, Donald Trump of the USA, Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey, Vladimir Putin of Russia, and Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow of Turkmenistan. Now, before you start typing away your complaints and protests (or throwing paper airplanes), hear the reason why: they were awarded for “using the Covid-19 viral pandemic to teach the world that politicians can have a more immediate effect on life and death than scientists and doctors can”. I’d say that makes you think quite a bit, especially as a person in the scientific community.

If you consider these instances in isolation, perhaps there is some point to what the former scientific chief advisor was saying, and that a serious researcher might not want to be associated with this prize (kinda like the Raspberry award, I guess?). However, this was apparently not a popular opinion, at least in the UK scientific community, which backlashed at the comment earlier. To this day, we get awardees from the UK in the Ignobel prizes.

Legacy beyond the funny and curious:

Parody and satire, yes, but in case you think this is still a long post for much ado about nothing, as it’s still in the realm of a joke, I want to present you this final case of when these jokes lead to “actual” science (not that they weren’t real science to begin with, but…). Take Andre Geim for instance, who shared the 2000 Ig Nobel in Physics with Michael Berry for levitating a frog – yes, a real frog – using magnets. Ten years later, he went on to win the actual Nobel Prize in Physics for his groundbreaking research on graphene. This itself may sound like a lucky coincidence but it is also worth mentioning that this frog experiment was reported in 2022 to be the inspiration (at least partially) behind China’s lunar gravity research facility.

These are not the only examples where such “silly research” actually ended up having real-world impact and use. In 2006, the Ig Nobel Prize in Biology was awarded to a study showing that a species of malaria-carrying mosquitoes (Anopheles gambiae) is attracted equally to Limburger cheese smell and human foot odor. This initial study was published in 1996, and the results suggested the strategic placement of traps baiting this mosquito with Limburger cheese to combat the Malaria epidemic in Africa. While these applications of the study might not be immediate, I think what allows for this translation (aside from being oddly specific) is partly due to the cost-effectiveness. The more typical “scientific” solution one might envision with disease control might involve genomics, vaccines, or pharmaceuticals. While they are all state-of-the-art and highly effective (and certainly have the sci-fi appeal), the cost both in terms of financial and time resources, can be expensive. Compared to that… cheese? I’m guessing that it’s more budget friendly and easy to implement. This research as well as this year’s award in biology about painting (zebra-like) stripes to cows as a mosquito repellent, all make me re-appreciate that sometimes the viable solution might be something unexpectedly simple and close at hand. These studies show how science, even in its quirkiest forms, can indicate practical and effective solutions to improve everyday lives.

Diversification of sci-comm tactics

Whether you admire the nobleness of the Ig Nobel, think it’s all fun and whimsy sci-comm, or avoid it altogether as an aspiring “serious” researcher, I think this still stands as a rare gem in the diversity of what science-communication can look like. In recent years, “debunking style’ science communication is seemingly (back) on surge, as well as various independent video-based science communication content creators (such as the guest speaker we had last week). In the age where science itself and its institutions are increasingly seen through a critical eye or outright contested, I do understand the urge to fact bomb or even isolate myself in all the “seriousness”. This is especially tempting when we know that some of the fruit of scientific research, like vaccines, can save lives, and we desperately want people to protect themselves. I personally don’t consider myself especially witty, but celebrate those who can masterfully blend research and humor to entice audiences and reignite their interest in science. Of course, not a single sci-comm tactic is bulletproof – some, like Sir Robert, may find these things distasteful, while others simply prefer something “serious,” and that’s ok. But science as a community might just benefit from having such a quirky tactic under its sleeves, and the diversity in science communication approaches might very well be the best shot we’ve got for this day and age of increasing division. Who knows, maybe some researchers will look into the efficacy of the IgNobel prize headlines against the science-anxiety.